“You wouldn’t realize modern big brands have a perish risk unless you were familiar enough to remember all the other things that perished that looked investable and permanent but they weren’t.”

That’s Charlie Munger, in what likely was his final recorded interview, which was broadcast less than two weeks ago, shortly after his death. (This should be on everybody’s “must listen” list.)

The interviewer was Stripe co-founder John Collision. Munger was talking about how well-known brands are probably more vulnerable than they’ve been in the past 100 years, thanks to the growth of private label and changes in retailing.

“And if you're an investor,” he added, “you should realize that – even though you haven't seen it yet. And you wouldn't realize that modern big brands have a perish risk unless you were familiar enough with economic history to remember all the other things that perished that once looked investable and looked permanent and, of course, they weren't.”

Mining the Past...

The timing of hearing his comments was perfect, especially after getting peppered by a bunch of charts from my pal Benjamin Brey of Deductive Capital, who manages his family office and consults for hedge funds and other professional investors. He’s also

here on Substack. Ben is part of my network of contacts, and spends more time than most mining the past to try to figure out the future... in an effort to maneuver through the present.His approach works for him. And macro guy that I am not, I enjoy the back-and-forth with those who are, because like it or not, it’s part of the equation.

I know what I don’t know, or as Munger laid out in that interview...

You have to know the edge of your competency. And if you know the edge of your competency, you're a much safer thinker and a much safer investor than you are if you don't know it. And I constantly meet people, better to have an IQ of 160 and think it's 150 than an IQ of 160 and think it's 200. That guy is going to kill you because he doesn't know the edge of his own competence and he thinks he knows everything.

Currencies, rates... Ben trades them and is first to admit “it’s complex and hard” for anybody who doesn’t and isn’t schooled in it.

But given his history of having run a bond portfolio for a university trust fund, where he was schooled on rates “from one of the best guys ever” – and also having been a stock analyst at Fidelity earlier in his career – he straddles both sides... “more one side than the other, depending on the market.”

And even then, Ben will be the first to admit that he hasn’t figured it out...

But a sense of history, while guaranteeing nothing, certainly can help...

Rate Roulette

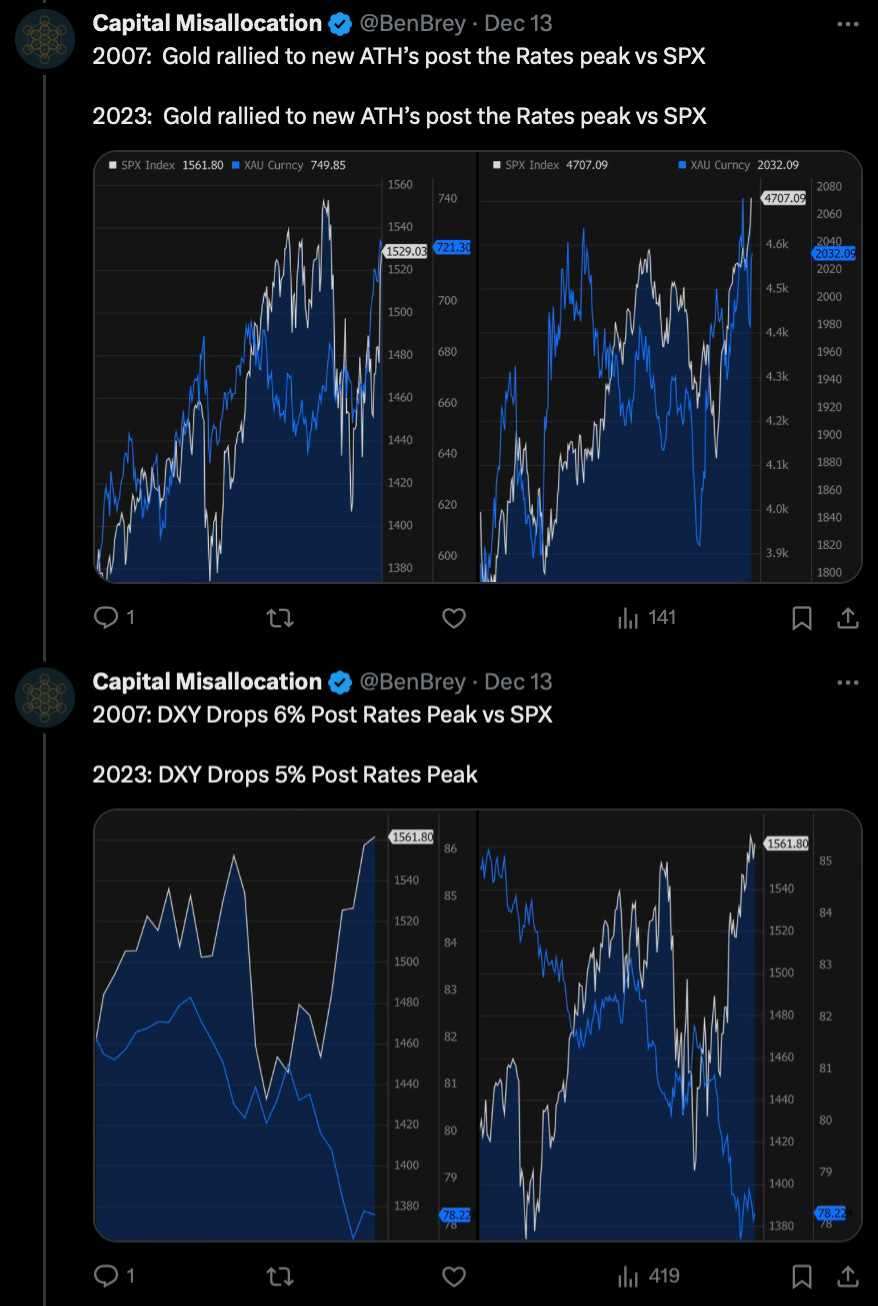

So, after stocks blasted off last week on the latest round of interest rate roulette, Ben sent over a New York Times clip from 2007, after the Fed cut rates by a half a point.

He went on to post a few charts on the former Twitter, where he is @benbrey of how the market started just before that rate cut in 2007 and how it ended a year later, with the Great Financial Crisis...

He added...

And...

The reality is, you can slice and dice the numbers any way you want in an effort to figure out whether history will repeat itself this time, or merely rhyme... or neither.

The Ultimate Trap

But that’s what makes markets. And when it comes to investing, outside of buying good businesses at good prices – however that’s defined – there’s no perfect approach or style. It largely depends on risk tolerance, personality, depth of real or perceived knowledge and a person’s overall wiring.

All of that is against the backdrop of human nature, and the fact that other than the most disciplined of the bunch – as Ben pointed out to me in our exchange – there’s the Pavlovian undercurrent that what worked before will work again.

Trouble is, that’s the ultimate trap. Or as Ben puts it...

Historically this hasn’t worked. Why would this be different this time? Most stocks over time don’t work, even most successful stocks eventually falter.

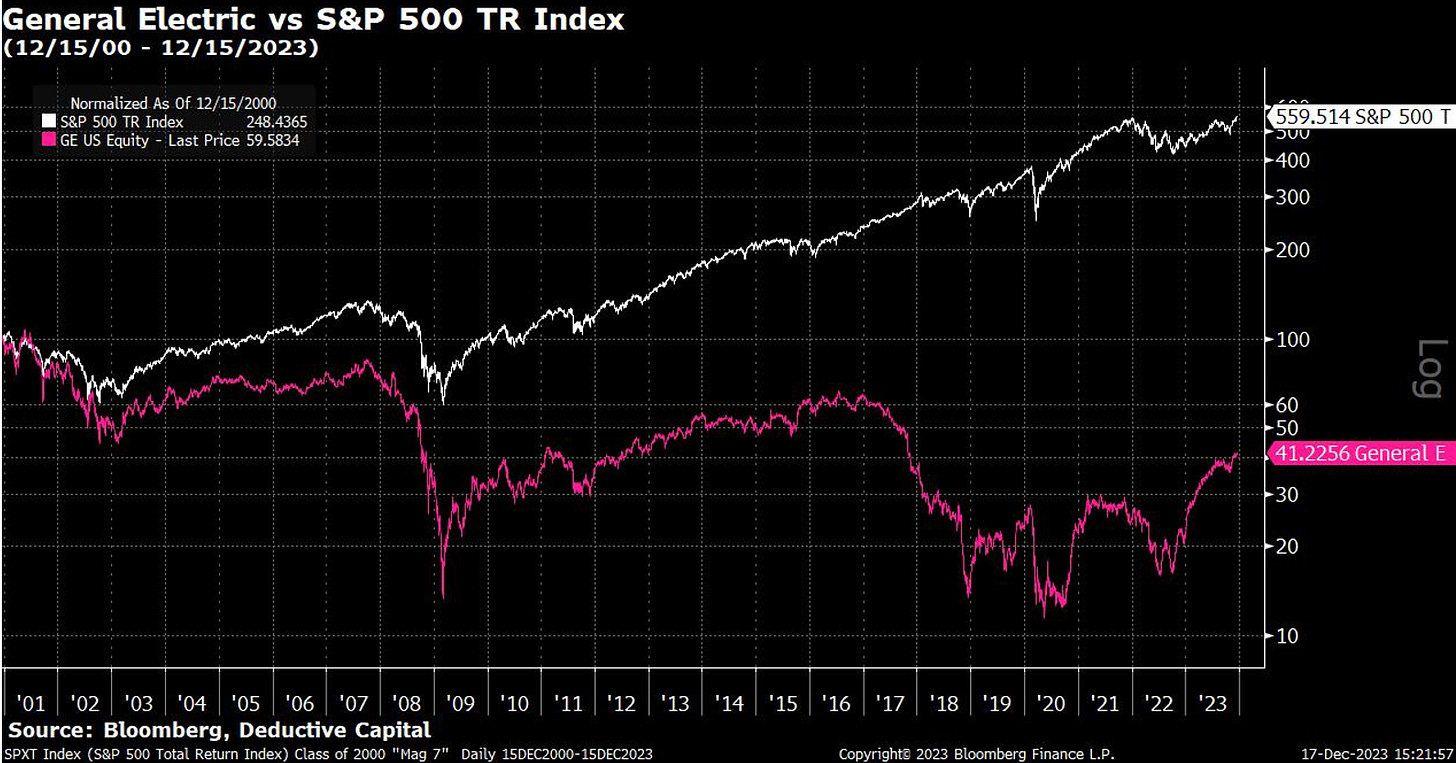

Just ask anybody who bought General Electric in 2000, a mere 23 years ago... for no other reason than it was GE – not only the best-performing stock for years, but the most valuable.

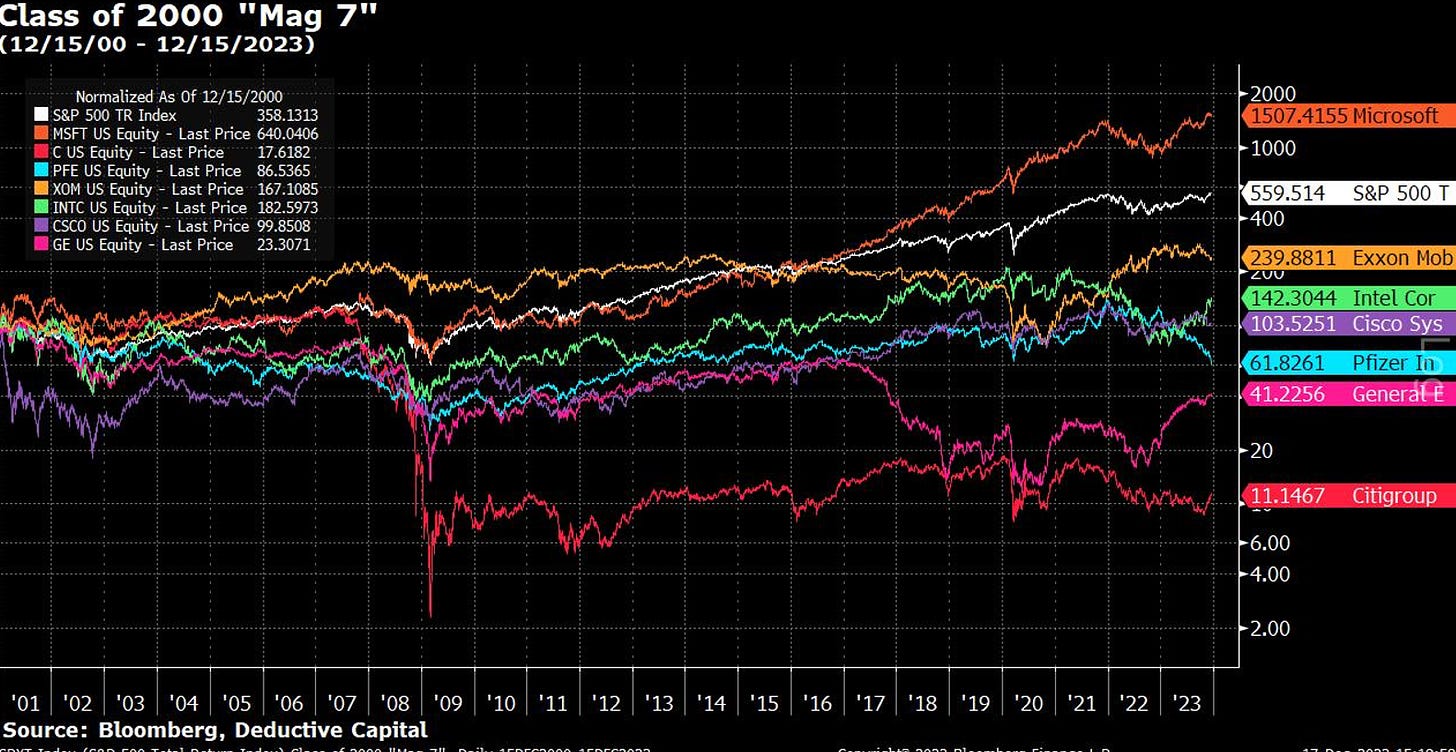

It was challenged in valuation by Microsoft, and then Exxon Mobil....

At points, even Cisco, Intel, Pfizer and Citigroup were in the running.

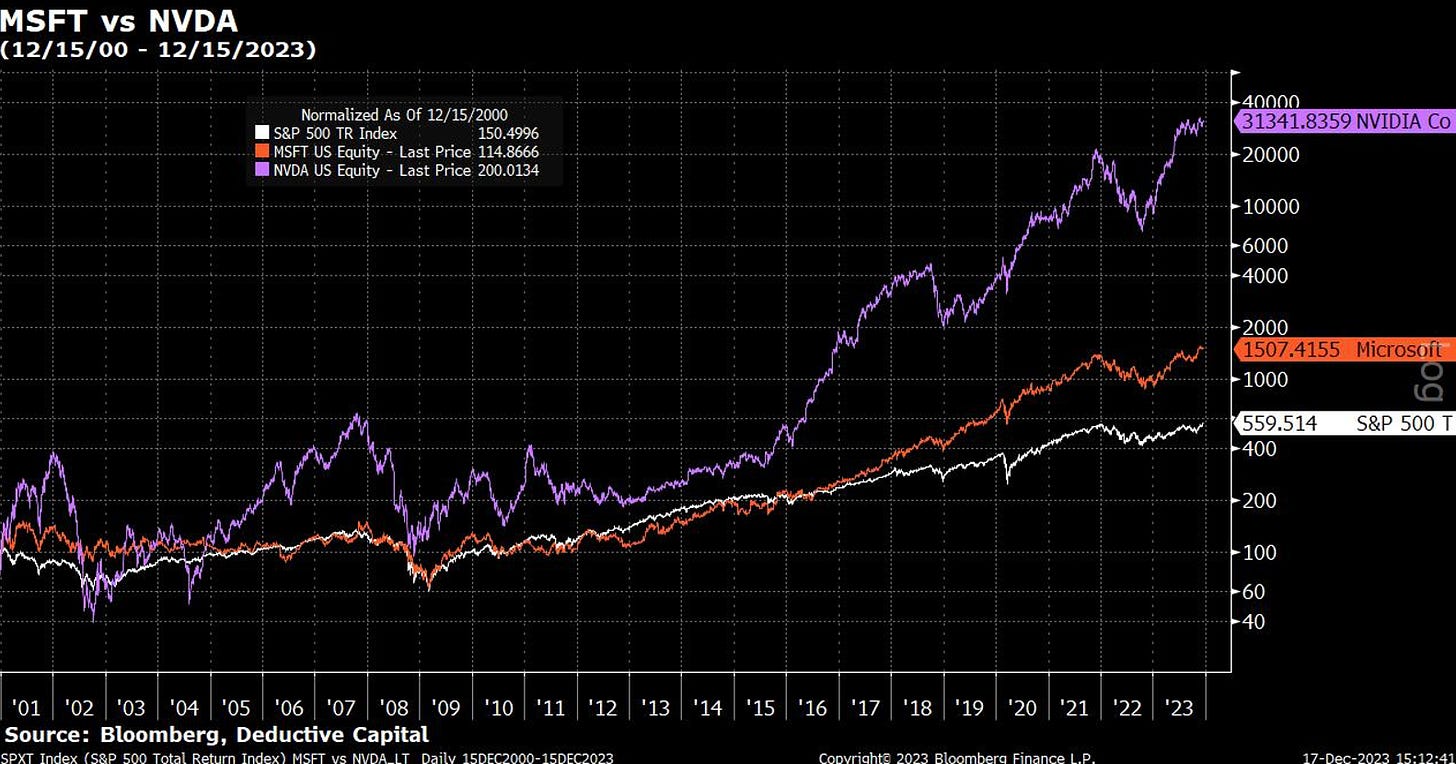

What’s clear, as Ben alludes to in the charts below, is that if you betted on GE at the peak of its popularity, you would’ve done much better simply by betting on the market.

As it turns out, if you look at the Magnificent 7 from the class of 2000, the market would’ve been a better bet than all but one... Microsoft.

I mean, really.... who back then had Microsoft on their bingo card to be the most valuable company in 2023? There’s no question it was an up-and-comer, but it was the only one that lived up to its expectations… and hype. And that’s after a few years of looking like a loser. Ironically, Apple wasn’t even among that era’s market cap monsters… and it turned out to be the biggest of all.

Now for the Bonus Round…

Of today’s Magnificent Seven, which would you bet on… for the next 20 years?

Apple (AAPL)

Alphabet (GOOGL, GOOG)

Microsoft (MSFT)

Amazon (AMZN)

Meta (META)

Tesla (TSLA)

Nvidia (NVDA)

For context, on a percentage basis, over all those years the gain in Nvidia’s market cap blows away the market and Microsoft...

And before you decide, keep in mind the following…

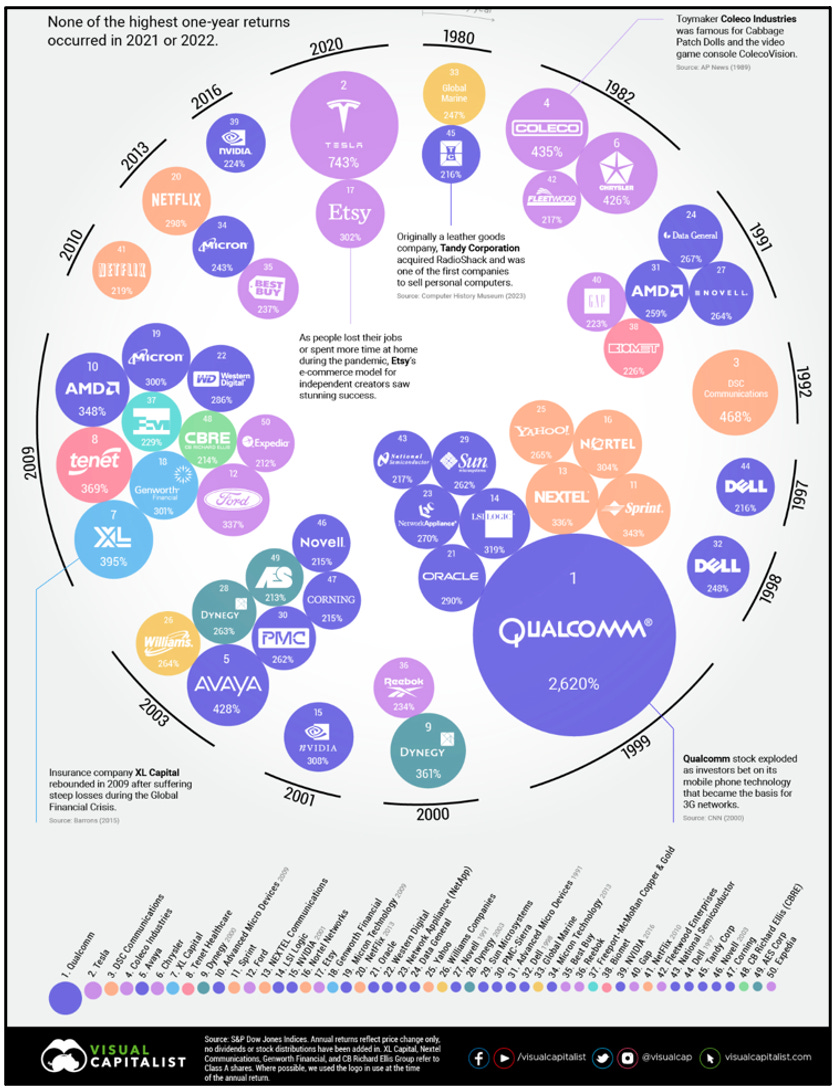

That’s right, no company in the S&P 500 has had a bigger one-year return since 1980 than Qualcomm, in 1999, rising 2,620%. Second is Tesla in 2020, at 743%. Nvidia, for what it’s worth – this year’s best performer so far, with a gain of around 234% – was the biggest gainer in 2001, with a 308% gain.

We could go on and on, but of today’s biggest and best, which will still be standing in the top echelon 20 years from now? Let me know in the comments below.

Finally, before we go, there’s one more point Ben mentioned that is worth sharing...

Running in Place

On my recent vacation, we went from Japan to Cambodia via Taiwan and Southeast Asia. Most of it was on a ship, and some of our touring was with small groups. But anytime you’re in a group, there’s lots of hurry up and wait.

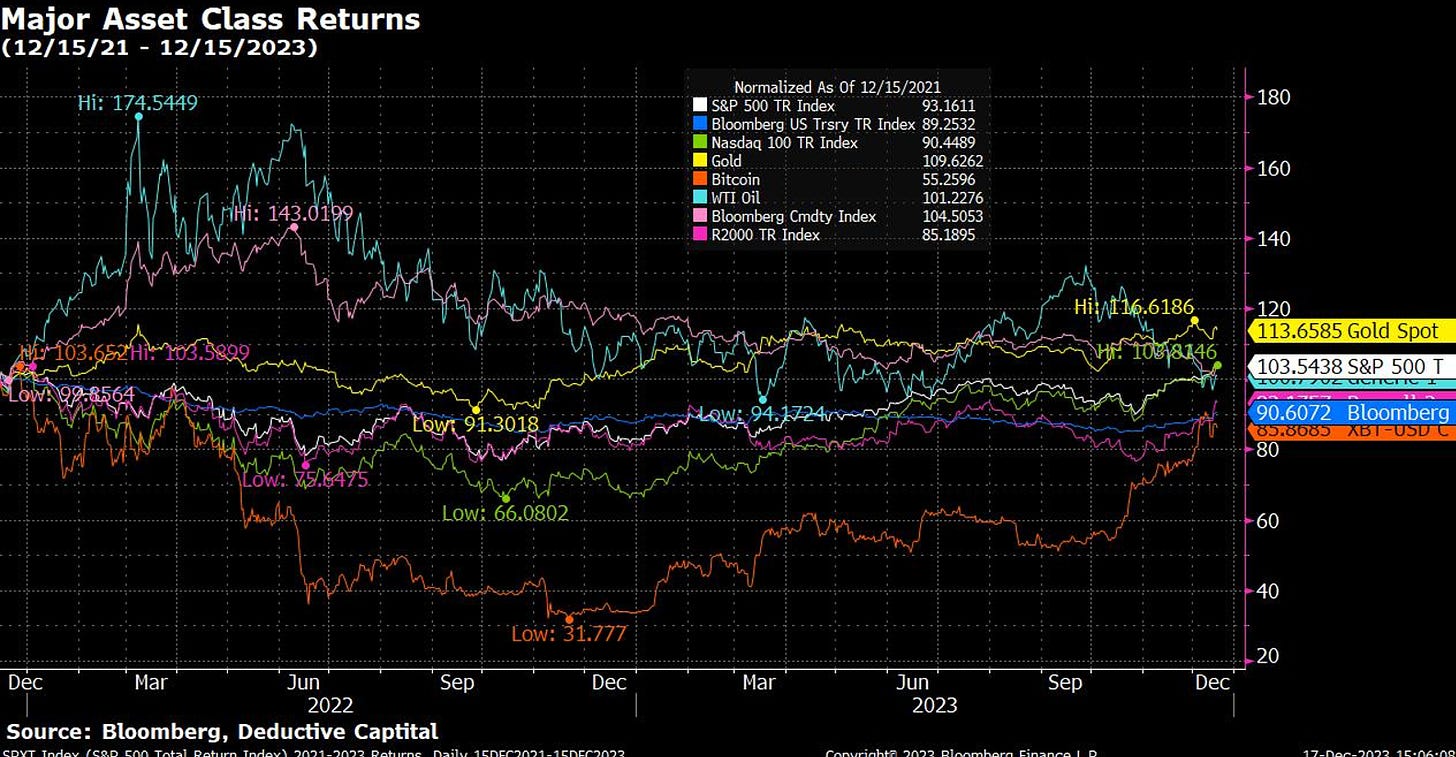

That’s the story of this market for at least the past two years, starting just before the meme/SPAC/everywhere bubble peaked...

And not just the stock market, but – fun fact – almost all markets. This chart from Ben shows it clearly.

In other words, as he explains...

Despite all the craziness of the last two years, here we sit with almost all asset classes Nominal returns up or down 10% of where they were in December 21.

He went on to say...

And depending on what you use for inflation everything is under water on a real basis except gold. But if you use higher inflation, estimate even gold is underwater. No escape.

There has been no real wealth gained. At best you are keeping up.

To me this makes the case for active management once again.

Maybe, maybe not. But it all harkens back to something else Munger said in that interview that can never be said enough...

I figure all investment is intrinsically damn difficult. Because obviously good ideas get bid to such high prices that they get dangerous… just because there's no investment that is so good you can't ruin it by raising the price higher and higher, because none of them are worth an infinite amount of money.

Amen.

As always, if you liked this, please click on the heart below. And please feel free to share this, and if you agree or disagree with anything you read here, feel free to add your thoughts in the comment section below. Thanks, Herb

DISCLAIMER: This is solely my opinion based on my observations and interpretations of events, based on published facts and filings, and should not be construed as personal investment advice. (Because it isn’t!)

Feel free to contact me at herbgreenberg@substack.com. You can follow me on Threads @herbgreenberg.

Netscape. Oh wait, AOL

Lol

AAPL