Case Study – Why the Story of Newell Matters So Much

How one company ran its investors through the Osterizer

Some stock stories stick with you more than others. For me, Newell is among them...

Maybe best known for its 1999 merger with Rubbermaid, later dubbed “the merger from hell,” Newell went through so many incarnations and acquisitions over the years that it can be hard to keep them straight.

It was like a corporate shell game, and that’s never a good sign…

No wonder Newell landed on the radar of the short research firm I was with in 2017, prompting us to publish a report in September of that year headlined…

Is Newell About to Get Run Through the Osterizer?

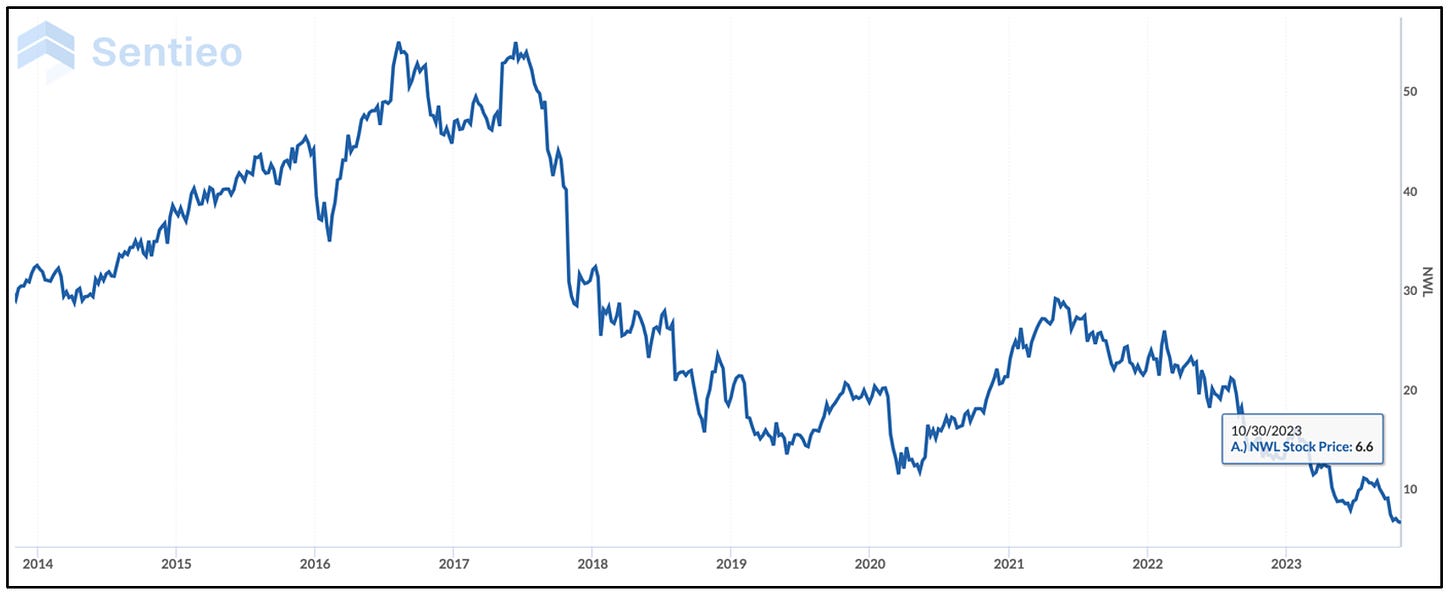

The stock had already taken a tumble on an earnings disappointment – not its first – but as we wrote, “red flags are flying everywhere we look.”

The pushback we received at the time, from a few subscribers, was that “the valuation has already compressed.”

Indeed it had, reflected by its stock, which had tumbled about 20% in the months before we published.

From Bad to Worse

Our work suggested something worse was going on...

That’s the trouble with the “compressed” argument, and why it’s a steady theme here. As Newell shows so clearly, just because a valuation has compressed doesn’t mean it can’t compress more.

And, boy, did Newell’s valuation compress... and compress... and compress.

It was 41 when we launched coverage, plunging another 28% on bad earnings news less than two months later.

Subsequently, nothing helped.

Not new management…

Not activists…

The business wasn’t just broken, its performance was an illusion... the result of management resorting to accounting sleight of hand in an effort to distract investors from seeing just how much management had boxed itself into a corner of overpromising on what it could realistically deliver.

In the end, it was outright (not to mention good, old fashioned) earnings manipulation.

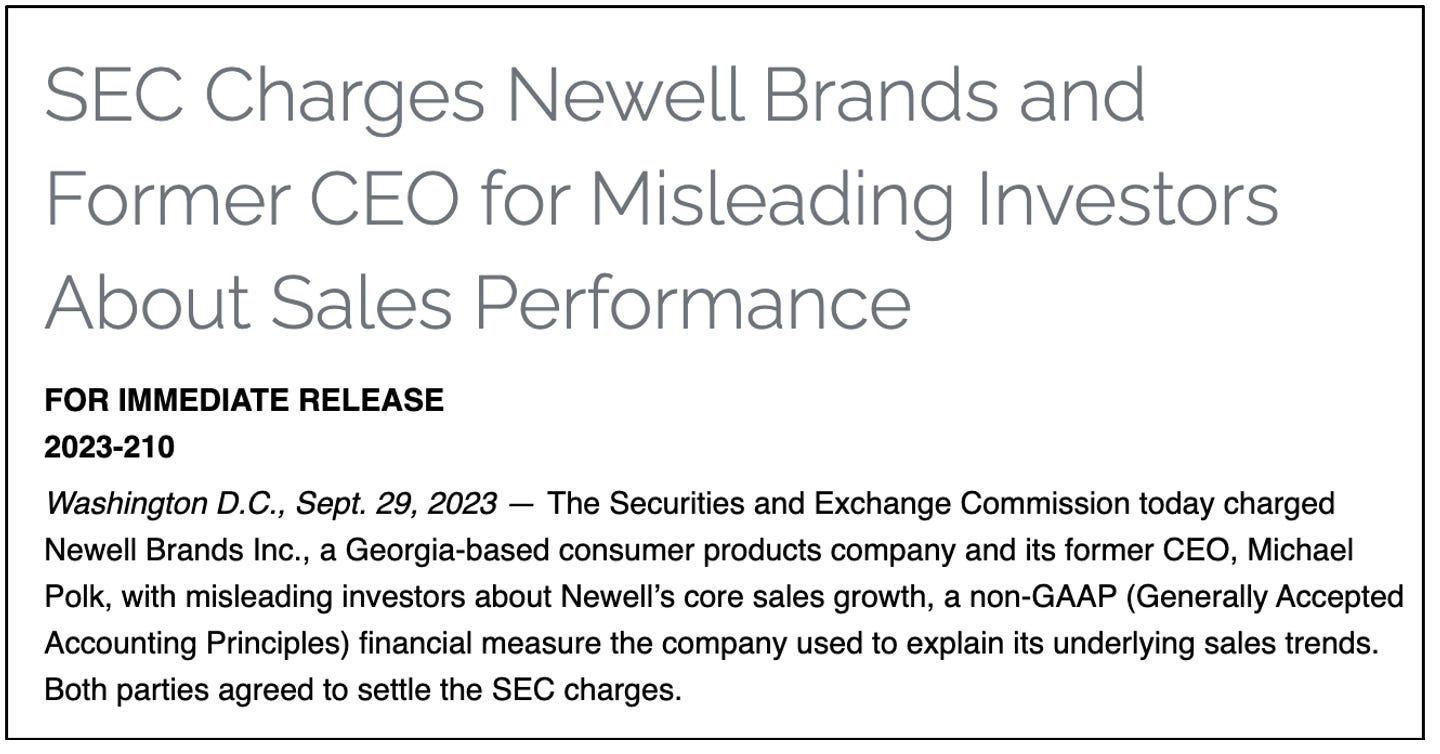

Enter the SEC

I hadn’t thought about this until a few weeks ago when Bill Whiteside and Jeff Middleswart at Peek Behind the Numbers here on Substack wrote a report headlined, “Newell Brands and the SEC – At Last They Meet.”

Long story short, the SEC sued Newell and ex-CEO Michael Polk for “misleading investors” in 2016 and 2017....

In other words, they lowered the boom six years after the fact, and nearly four years after the company first acknowledge receiving a subpoena related to the issue. As is usually the case, both sides settled.

This would’ve been an easy one to miss, because it happened so long ago. And Newell at this point is not what I’d call a made-for-TV name.

There’s also the fact that investors generally roll their eyes at SEC investigations, since they’re often so long after the fact, as was the case here.

But they’re important, if no other reason that serving as a reminder how far even today management will go to make things look better than they really are.

‘Scrubbing’ the Accruals

This is such a textbook case. From the SEC’s press release:

Newell and Polk took actions that increased the company’s publicly disclosed core sales growth in ways that were out of step with Newell’s actual but undisclosed sales trends, allowing the company to announce “strong” or “solid” results in quarters it internally described as disappointing due to shortfalls in sales.

What’s more...

Newell pulled sales forward into earlier quarters without adequate disclosure and engaged in accounting practices that were inconsistent with GAAP, while overriding its internal accounting controls. Collectively, these measures gave the misleading appearance that Newell had achieved core sales growth in line with its targets and deprived investors of information relevant to an accurate and complete understanding of Newell’s actual sales trends.

The press release went on to quote Mark Cave, associate director of the SEC’s division of enforcement, as saying that Polk “issued an instruction to ‘scrub’ the company’s accruals after he learned that the company was projecting a ‘massive’ and ‘disappointing’ miss for the quarter.”

Size Doesn’t Matter

The best part, as Bill and Jeff point out… this wasn’t some puny company, where it’s not uncommon to find these kind of shenanigans.

When we first wrote about it, Newell’s market cap topped $20 billion...

Today it’s $2.7 billion.

And as Jeff and Bill go on to say, this isn’t an isolated case among big companies...

Surveys of CFOs have indicated that they believe that in any given year 20% of companies have materially overstated their earnings even though they have adhered to GAAP. Now consider that we live in a world where well over 90% of companies are being valued on non-GAAP results that have been adjusted by the companies themselves to make them more ‘realistic.’

They go on to point out that the real risk isn’t that the SEC ultimately catches on. Let’s face it, they’re often the last to know, but that’s not the point...

The risk is that after several quarters of ‘stretching the rubber band’ to meet earnings targets with aggressive accounting choices and unrealistic adjustments, the organic growth never comes back, and the company finally reports the string of disappointing quarters that drive the stock down 20%. There may never be investigations, charges, and penalties, but the unexpected losses are still very real.

The irony is that a few decades earlier, Newell had a reputation as being a conservatively, well-run company.

Now it will be a poster child for just the opposite.

As usual, if you enjoyed this, please click on the heart below and feel free to share it with friends.

DISCLAIMER: This is solely my opinion based on my observations and interpretations of events, based on published facts and filings, and should not be construed as personal investment advice. (Because it isn’t!)

Feel free to contact me at herbgreenberg@substack.com. You can follow me on Twitter and Threads @herbgreenberg.

Yes great throwback - followed newell for years. There was a great pic on X with a couple (halloween costume) the man as ebitda and the woman as adj ebitda - not a fan of the adjustments - if you adjust every qtr its not adj its part of your poor business model - great piece!

Love this (unfortunately from the perspective of someone who bought into Polk). What’s the moral? Avoid companies that are doing any adjustments - how else do we know it’s a fraudulent adjustment versus legit.