The Handmade Tale

And have you ever been told you have a 'heart murmur'? If so, check out "the backstory" below...

Note: If you’re new to Herb on the Street, welcome! I tend to focus on business, investing and finance, but from time-to-time I like stray and share other parts of my life. This is a revised version of one of my favorites.

Please share with friends who have artificial valves, especially those who joke about being part cow or pig. I’m sure they’ll enjoy it.

– Herb

If you've ever had a new knee, hip, or maybe a stent to open clogged arteries in your heart, you probably never thought about what company made it...

Let alone who made it.

I know, because it was the last thing on my mind when I had surgery three years ago to replace my aortic valve.

I knew the valve I would be receiving was made by Edwards Lifesciences, which is the largest manufacturer of biologic heart valves. That's only because I spent years researching the inevitable… reading every study, story and forum I could find regarding heart valves.

Beyond that, I never gave a thought to how the valve was made, or even more granularly, the people who actually made it.

That was until fairly recently, when I made the hour-long drive from my home in San Diego up to the Orange County headquarters of Edwards...

I was there for something the company calls the "Patient Experience."

This is an annual two-day event, bringing in about 60 patients from across the country who have received all types of valves... either by open-heart surgery or by one of Edwards' transcatheter procedures.

A transcatheter replacement, as its name implies, involves a valve replacement done by snaking a catheter through the groin to the heart.

The procedure, pioneered by Edwards, doesn't require your heart to be stopped, which in turn means you don't need to be hooked up to a heart-lung machine. There's no question it has revolutionized the way valves are replaced, in the process revitalizing the valve industry.

As luck would have it, I wasn't a candidate for a transcatheter aortic valve replacement, or TAVR as it is more commonly called. That’s because I hit the jackpot and needed a bigger overhaul. As a result, mine was done the old-fashioned way, with a nine-inch incision so my ribs could be pried apart.

But here's the thing...

It doesn't matter how the procedure is done... the valve is made pretty much the same way.

And as much as I researched valves and the procedures before my surgery, reading anything and everything – including ever study I could find and watching videos of surgeries – I was humbled to learn what I didn't know...

And by the stories of others I met whose lives in all likelihood would have been cut short if artificial valves didn't exist...

Like my new friend Dennis, who owns a large date farm just south of Palm Springs, California and flies his own plane. His heart valve had been damaged by endocarditis – an infection – and he had no choice but to have a new valve surgically implanted...

Or the woman I met at lunch who had a repair of her mitral valve via a robot, but wound up getting a rare complication in the form of a blood disease that almost killed her. She ultimately needed a full surgery to replace the valve. She looked as good as new, even though six weeks earlier she was on her deathbed...

Or the 71-year-old guy from Massachusetts who runs a small packaging business, but whose real passion is playing wind instruments. His tricuspid valve, one of the four valves we all have, had been malfunctioning. He was having trouble putting one foot ahead of the other, let alone playing his instruments. He became the 20th person to have transcatheter replacement of his tricuspid valve as part of an Edwards trial. He said he felt like new the next day, and could play wind instruments again. When I last saw him, he was on his way to the airport in Los Angeles to take a red eye back to the East Coast for a meeting the next day.

What we all had in common was that we all were satisfied owners of an Edwards valve, which was made either in California, Singapore, or Costa Rica.

And we were all there for the same reason... to see how our valves were made, but more importantly, to meet (either virtually or in person) the actual people who physically made them.

And that's the part of this entire visit that resonated the most...

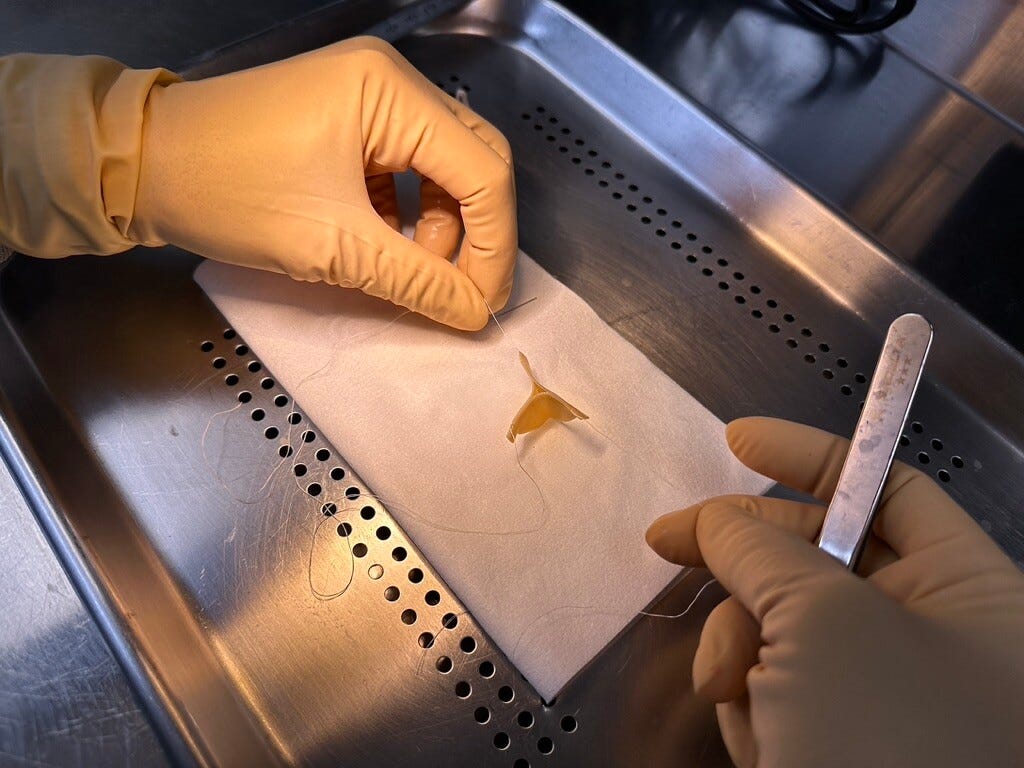

Artificial valves are not produced on machines. It's all a very hands-on process, with zero automation. Each valve is hand-sewn using around 1,000 stitches in a clean room assembly line (like the one below in Irvine) by a team of around 10 people, who pass it along in process and quality control that can take five to 15 hours. Training takes six months.

Most of the sewers are from Southeast Asia... and some are second and even third generation. All of the sewing is done while looking through a powerful microscope.

As we were taken through the process, I took photos...

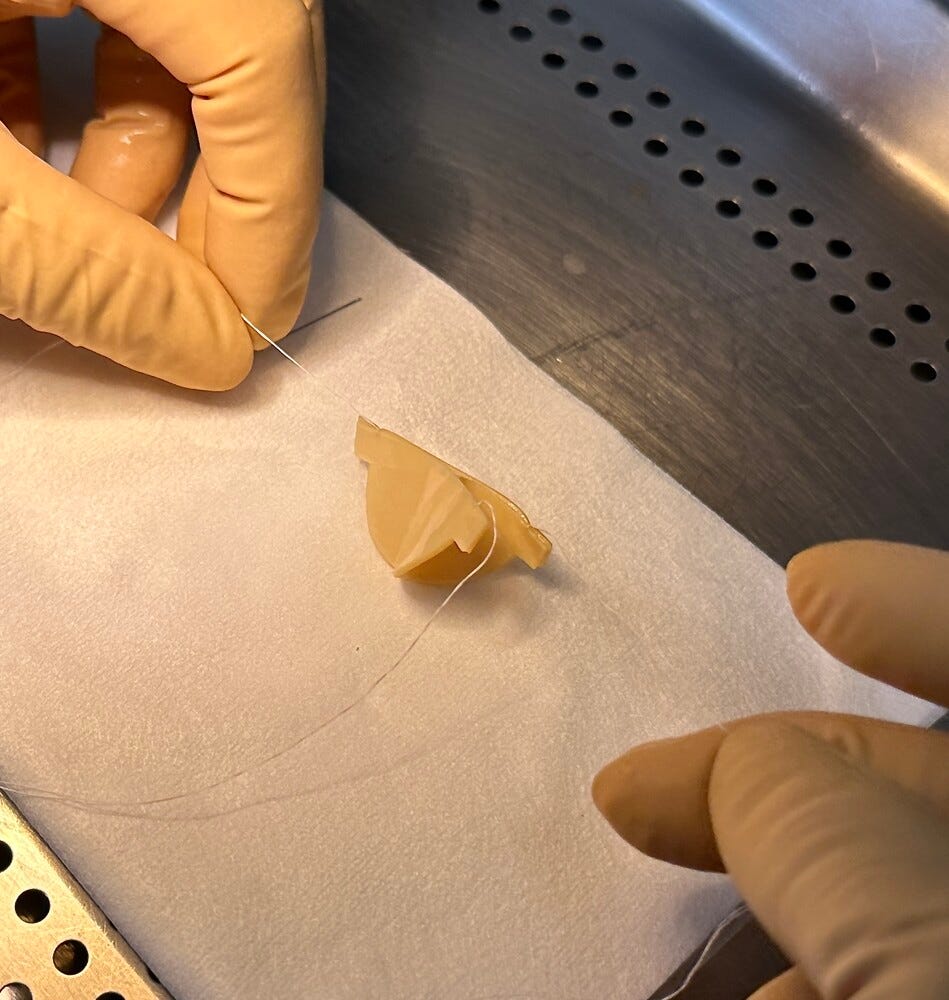

The first step is sewing together three leaflets made from a processed pericardium of a single cow. (In the pictures below, those hands are of a trainer who started as a sewer 30 years ago. I was matched with her to get an up-close look of how the sewing is done.)

Those leaflet pieces are then sewn onto a fabric base, which is then sewn onto a fabric-covered frame and base made from alloy wire.

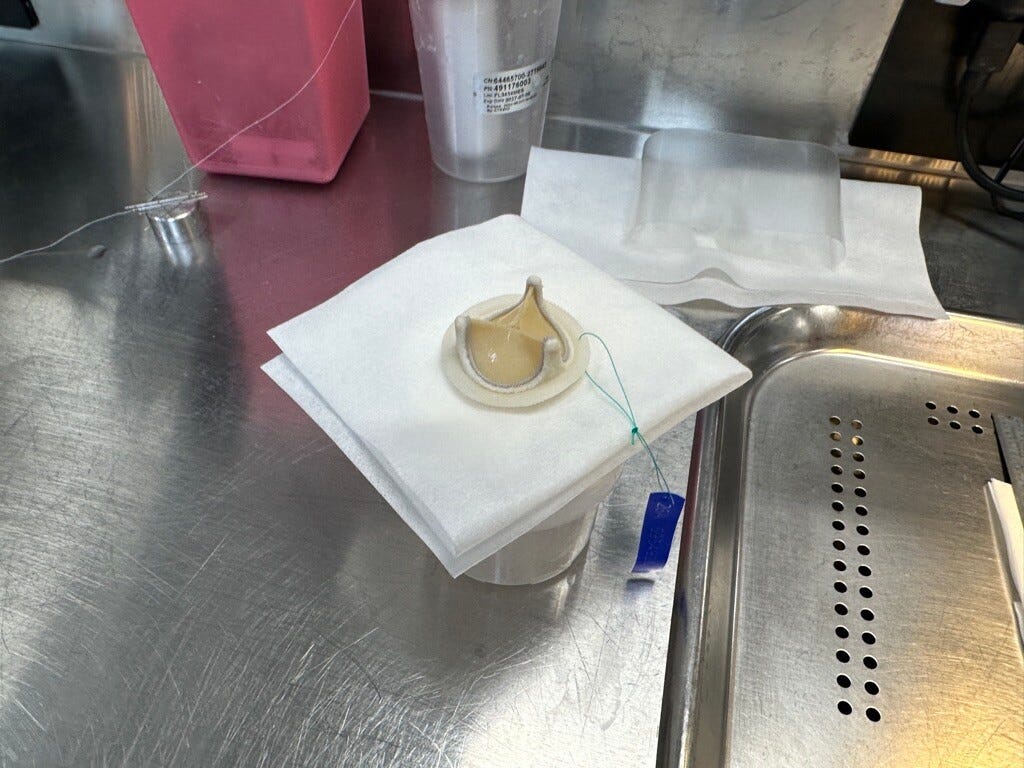

The result is a heart valve like the one below, which is the same model as the one beating inside of me.

It's tedious work...

Edwards holds these events in large part as a morale booster, so employees can put a face and person to the work they do.

It's also good PR. It's one thing to meet the person who worked on the world's tallest skyscraper or perhaps made your car, but it's another to meet the people who made the heart valve that's keeping you alive.

The highlight, of course, was meeting the three wonderfully talented and kind women who were part of the team that sewed mine. We were matched by the serial number on my valve.

Being able to look them in the eyes and personally thank them and tell them about me, my family, my grandkids... I'm not sure who was more emotional, them or me.

The Backstory…

I first learned of my heart issues more than 40 years ago, when I was told I had a heart murmur during a routine physical. That’s when the doctor, using his stethoscope, hears a click, which indicates blood is leaking back into your heart. Like many people, I was told “not to worry,” but I demanded an echocardiogram to get more information. At the time I was in an HMO and had to fight the system, which I did…

From that point on, I had my valve checked every year with an echo, which is a painless ultrasound.

My advice is that if you are ever told you have a murmur and “not to worry,” get yourself a second opinion… preferably from a cardiologist.

Here’s why…

While most people who have murmurs don’t or won’t eventually need surgery, it’s important to know exactly what kind of valve you have. Unfortunately, heart valve disease is woefully under-treated. That’s because not everybody has symptoms, yet with or without symptoms, damaged and untreated valves can lead to heart failure.

I was in the asymptomatic group, but thanks to annual echos I watched the slow and silent deterioration of my heart’s performance over the years, hoping to catch things before there was any irreversible damage.

But there’s something else that you need to know…

It’s not just knowing you have a murmur; if your aortic valve is the “leaky” one, it’s important to know how many leaflets your valve has. You’re supposed to have three, but 2% of the population has two.

I was told I was in that exclusive group, and I’m sure glad I knew because as it turns out, anybody with a bicuspid valve is more prone to having an aneurysm of your ascending aorta. That’s the hose blood pumps through after leaving your heart on its way to the rest of your body. An aneurysm means it’s staring to expand, and if it gets too big… kaboom!

Lucky me, in addition to the bad valve, I had an aneurysm!

To lower the chances of it bursting, for years I would get MRI scans measuring the size of my aorta… watching it slowly grow and grow.

Then came the magic moment…

Thanks to Dr. Eric Topol at Scripps Clinic in San Diego, who writes Ground Truths on Substack, I had been sending the results of my echos and MRIs to the Cleveland Clinic for several years to get a second pair of eyes. Eric used to be at Cleveland, and I had interviewed him several times during my journalism career. When I realized where things were likely headed it was only natural that I included him as a consulting cardiologist. He suggested that “when the time comes” I include Cleveland in the mix.

“Not yet,” was always the response from Cleveland, until January 2020, when I had my annual in San Diego. This time, I was noticing some things and starting to feel a little off. I was getting tired of hearing my cardiologist say, “let’s check it again in three months.”

By then I was on what I like to call the “every three month scan plan.” My wife and I like to travel, and the wildcard of “not if, but when” I would need heart surgery was starting to get in the way.

Turns out, that was about to change. I’m a big fan of listening to your body, and this time the message from Cleveland was that I should fly out for an in-person consultation and have additional tests.

A month later I did just that and met with Dr. Lars Svensson – the chairman of the Cleveland’s Heart and Lung Institute... and a surgeon's surgeon, if there ever was one.

After reviewing everything, he told me my valve was failing and should be replaced.

I wondered if we could wait until August, after my first grandchild was born. Dr. Svensson, who would never be mistaken for a comedian, looked me straight in the eyes and said calmly but sternly, "I would do it now."

I was back in a month, just before the pandemic hit.

Lights out time in the operating room was around five hours. At some point they stopped my heart to replace the valve. During that time, I was on the heart-lung machine for a little over an hour.

The biggest surprise: I didn’t have a bicuspid valve, after all; instead, I had an even rarer unicuspid valve… that means my aortic valve had just one flap. At the time I was 67; those are usually found and replaced by the time somebody is in their 30s, at the latest.

Had I not been keeping tabs on this, by now I would probably be on my way to heart failure.

The very concept of how somebody conjured up the idea of an artificial heart valve remains a baffling marvel, but so is the fact that I have an artificial valve, a new artificial aortic root, and a Dacron repair of my ascending aorta... none of which I would even think about if I didn't have the faded scar as souvenir.

I now have two grandkids and as corny as it sounds, I consider myself one of the lucky ones who found out I had a problem… before that problem found me.

Onward…